Film is more than just entertainment — it’s storytelling through visuals, sound, and emotion. And just like in English literature, there’s a language to it. Whether you’re studying The Truman Show, Gattaca, or Billy Elliot, learning how to analyse film techniques is essential for HSC success.

To analyse film, we must first be familiar with the world of film techniques. Think of film techniques as the cinematic equivalent of literary techniques. But instead of similes and metaphors, you’re looking at camera angles, lighting, sound, and editing. These techniques help directors construct meaning, shaping how you see a character, feel a mood, or understand a theme.

Note that these are commonly used techniques, and this is not an exhaustive list. Consider any technique lists given by your teachers, or find more complex techniques online!

Camera angles refer to the tilt or positioning of the camera to portray the scene and characters. Think of the angle as the audience’s point of view.

Low Angle

Filmed from below the subject, low-angle shots make characters appear dominant, intimidating, or heroic. They physically elevate the subject, often reflecting their status or strength.

Mid Level

Also known as an eye-level shot, this is the most neutral camera angle, often used in conversational scenes. These shots place the viewer and character on equal footing, promoting empathy and emotional resonance.

High Angle

High-angle shots look down on a subject, making them appear smaller, weaker, and more vulnerable.

Dutch Angle (Tilted Angle)

A Dutch angle, or tilted shot, skews the camera so that the horizon is slanted. This framing often suggests unease, instability, or psychological tension, and is used to disorient the audience and foreshadow conflict.

Over-the-Shoulder shot

An over-the-shoulder shot is filmed from behind a character, focusing on what they’re looking at. Often used in dialogue scenes to show perspective and connection, it builds intimacy and can reflect power dynamics depending on which character the audience is aligned with.

Aerial Shot (Bird's Eye View)

Taken from directly overhead, this shot provides an abstract or omniscient perspective. It can make characters look small and insignificant, suggesting fate, surveillance, or the power of the setting.

Shots describe how far the camera is positioned from characters or objects in a scene.

Establishing Shot

An establishing shot is typically a wide or distant shot placed at the beginning of a scene to set the location or context. It serves as an orienting device for the audience.

Wide Shot (Long Shot)

A wide shot frames the entire subject, usually a person from head to toe in the context of a large background. The emphasis is on the character in their environment. It shows scale, movement, and body language.

Close-up Shot

A close-up tightly frames a character’s face or a specific object to highlight detail and emotion. It allows the audience to closely observe expressions and connect with the subject’s inner feelings.

Panning Shot

A panning shot involves the camera moving horizontally across a scene from a fixed position. It’s often used to follow a character’s movement or to reveal more of the setting gradually.

Zoom Shot

Zooms involve adjusting the camera lens to make the subject appear closer or farther away without moving the camera itself. It can be used to emphasise emotion, reveal detail, or create dramatic or comedic effect.

Mise-en-scène

Mise-en-scène refers to how things are arranged within the frame, including setting, lighting, costume, and actor positioning. These arrangements create meaning and atmosphere, shaping the visual world of the film and often reflecting a character’s inner state or reinforcing key themes.

Visual Motifs

Visual motifs are recurring images, symbols, colours, or shot types that appear throughout a film to reinforce central themes or ideas. These intentional directorial choices help visually unify the narrative. For example, mirrors might repeatedly appear in a film to reflect themes of identity or duality.

Colouring

Colouring is the deliberate use of colour palettes to create atmosphere, reveal character, or symbolise abstract ideas. Monochromatic schemes can suggest minimalism or bleakness, while vibrant colours can convey joy, intensity, or artificiality. Directors often assign specific colours to characters or moods to help guide audience interpretation.

Lighting shapes the emotional tone of a scene and directs the audience’s focus. Low-key lighting, with deep shadows and strong contrasts, creates tension or mystery — often seen in thrillers and noir films. High-key lighting, which is bright and evenly distributed, conveys openness, honesty, or warmth. Chiaroscuro lighting uses strong contrast between light and dark to dramatise conflict or inner turmoil.

Diegetic Sound

Diegetic sound originates from within the world of the film — it includes dialogue, footsteps, background noise, or music that characters can hear. It grounds the scene in realism and helps create a believable world. When used symbolically (e.g. repetitive footsteps), it can also build suspense or reflect psychological states.

Non-Diegetic Sound

Non-diegetic sound is added for the audience’s benefit and isn’t heard by the characters — this includes background scores, narration, or sound bridges. It is often used to cue emotional responses, establish themes, or foreshadow events. For example, a melancholic score playing over a happy scene can suggest underlying tension.

Music

Music in film, whether diegetic or non-diegetic, plays a vital role in influencing tone, emotion, and pacing. It can heighten drama, reinforce mood, or connect scenes thematically. Iconic scores, like those in Inception or Harry Potter, can also become motifs tied to specific characters or themes.

Dialogue

Dialogue drives plot and reveals character psychology, relationships, and social dynamics. Its delivery, pacing, and subtext can be just as revealing as what is said. Silence or awkward pauses within dialogue can also powerfully express conflict, tension, or emotional distance.

Voiceover

A voiceover is narration layered over visual scenes, often from a character’s perspective or an omniscient narrator. It can provide exposition, internal monologue, or reflective commentary. Voiceovers are commonly used to guide interpretation or add emotional depth.

Sound Motifs

Repeated audio cues such as a ringing bell, ticking clock, or whispering wind, acquire symbolic significance over the course of a film. They can evoke memory, tension, or emotional triggers. When recurring, these sounds link different scenes and ideas, often reflecting the protagonist’s internal state.

Montage

A montage is a series of short, often thematically linked shots edited together to condense time, emphasise progression, or juxtapose ideas. It is frequently used to show character development, training, or transformation across time. Classic examples include the training montage in The Karate Kid or the passage-of-time montage in Up.

Filtering

Filtering involves digitally or optically altering the colour, brightness, or texture of footage during post-production. It can distinguish flashbacks from the present, represent a character’s subjective view, or establish tone. For example, cool blue filters to signal detachment or nostalgia, or golden hues to suggest memory and warmth. Filters shape not just how a film looks, but how it feels emotionally.

Analysing a film can seem overwhelming at first, especially when so much is happening on screen; visually, aurally, and emotionally. However, by approaching your viewing process strategically, you can break the film into manageable, analysable chunks that directly support your arguments in essays or multimodal responses.

While it may be tempting to dive straight into technical analysis, your first viewing should be about immersing yourself in the narrative. Watch the film uninterrupted, and absorb the characters, the story, and the atmosphere. Focus on understanding the broader picture: What is the plot? Who are the main characters? What conflicts arise? What themes seem to emerge?

This initial engagement allows you to grasp the film’s core ideas and provides essential context for the techniques you’ll later unpack.

Immediately after your first viewing, take 10–15 minutes to jot down any strong impressions, emotional responses, or key ideas. Ask yourself:

This is not about deep analysis yet- just noting moments that may warrant closer inspection later.

On this rewatch of the film, start actively observing the film through an analytical lens. If possible, watch in split-screen mode or with the subtitles on to make notetaking easier.

Pay close attention to:

This is the time to begin connecting technique to theme. Don’t worry about writing full analyses, just record your observations and impressions alongside timestamps for easy revisiting.

Once you’ve identified key scenes, use later viewings to pause, rewind, and zoom in on the details. Look for examples and unpack the details. Ask yourself:

Here, your focus should shift from what is happening to how it’s constructed, and, more importantly, why. If a technique does not contribute meaningfully to the film’s message or character development, it may not be worth including in your essay.

When exam season rolls around, the last thing you want is to be frantically flipping through pages of messy, disorganised notes — or worse, rewatching the entire film just to find that one technique again.

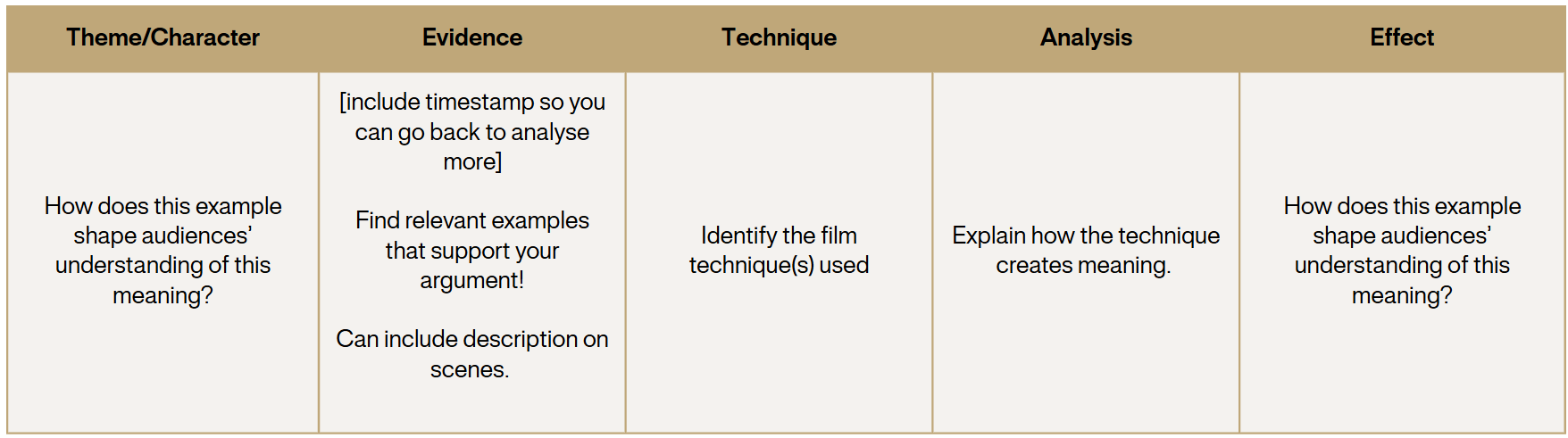

Consolidate your observations into a structured document or table. Organise by theme, character, or sequence, whichever best suits your essay focus. For example, a table like this could be used to collate your notes:

Remember, your ultimate goal is not to list techniques, but to demonstrate how those techniques construct meaning. Always link your observations to the film’s thematic concerns, character arcs, or directorial intent. Ask yourself:

Strong film analysis is not about noticing everything, it's about selecting the right things, and making them work hard for your argument.

To analyse a film effectively, it’s crucial to understand the conceptual focus of your module – the lens through which you’re meant to interpret the text. Just as you would with the author of a novel or poem, studying a film involves identifying key ideas, concepts, and values that the director is exploring. These ideas are almost always never stated outright, but rather embedded in the techniques. Whether this be low angle shot to show powerlessness, the use of colour, or the rhythm of the soundtrack. These directorial choices reflect a character’s inner world or the film’s broader thematic concerns.

It’s important you categorise the evidence and techniques to the themes you have identified, or the characters that these ideas align with. When analysing a scene, always ask: Why this technique, in this moment? A recurring motif, like the colour red or ticking clocks, might symbolise urgency, fear, or control.

For instance, if a film explores the theme of freedom vs control, you might notice how confined spaces (mise-en-scène), rigid framing, or repetitive sound motifs reinforce that idea. Likewise, characters often evolve visually, where the lighting around them might brighten or dim as they grow, relationships might shift in camera positioning, or their costumes might reflect internal change. The best essays don’t just identify techniques — they explain how these techniques reveal character and express theme.

Ultimately, strong analysis stems from how cinematic form expresses thematic meaning and shapes character development. The more fluently you can link technique to concept, the stronger your argument will be.

Behind every film lies a series of deliberate choices — not just in how a story is told, but why it is told at all. Understanding a director’s intent involves going beyond what is shown on screen and considering the broader purpose, historical moment, and personal or political motivations that shape the film’s creation. Directors are not simply storytellers — they are cultural commentators, and at times, provocateurs.

To uncover directorial intent, consider: What is the filmmaker trying to say? Is the film responding to a historical event? Is it critiquing a social structure, celebrating a particular value, or challenging a dominant narrative? Often, the techniques used, whether a recurring visual motif, a specific camera style, or a choice in sound design, are expressions of the director’s worldview or artistic philosophy.

Context plays an equally important role. For example, George Clooney’s Good Night, and Good Luck is not just a period film set during the McCarthy era; it is also a critique of contemporary media responsibility in a post-9/11 world. Clooney’s use of black-and-white cinematography, archival footage, and minimalistic set design not only situates the film historically, but stylistically reinforces the blurring line between journalism and state power. Given Clooney’s background in journalism and his open beliefs on political accountability, this adds further dimension to the film’s message.

When writing about directorial intent, it’s not about guessing what the director was thinking — it’s about drawing informed conclusions from the film’s form, content, and cultural context. Understanding the “why” behind the “how” is what transforms good film analysis into great film analysis.

Film analysis isn’t just about spotting techniques — it’s about uncovering meaning. Every shot, sound, and design choice serves a purpose, revealing something deeper about the story, characters, or themes. By learning to read these visual and auditory cues, we move beyond passive viewing and begin to engage with film as a complex, layered text. The more purposefully you connect technique to idea, the stronger and more insightful your analysis will be!

We provide specialised English tutoring for students in Years 7 to 12, helping them build strong foundational skills, master the NSW English syllabus, and excel in HSC English.

Yes, all our lessons are carefully aligned with the NSW English syllabus. ensuring students are fully prepared for school assessments, exams, and HSC English requirements.

We start with an Introductory Lesson to assess each student’s strengths, weaknesses, and learning style. Our English tutors then design personalised lesson plans aligned with the NSW English syllabus to ensure targeted learning.

All our classes are one-on-one. This allows us to accommodate different learning preferences, ensuring each student receives the attention and support they need.

Absolutely. Our tutors are experienced in guiding students through preparing for specific assessments, exams and assignments, providing targeted feedback and strategies to help them succeed.

Yes, we provide weekly content, comprehensive resources, including practice materials, worksheets, and model responses, to help students consolidate their learning and practice independently.

Typically, each session is 90 minutes. Our termly courses are at least once a week, but the frequency can be tailored based on their needs and academic goals.

Yes, we offer both in-person and online tutoring to accommodate different preferences and ensure flexibility in learning.

Yes, we offer new students an Introductory Lesson with no obligation to continue. This allows new students to experience our teaching approach, meet their tutor, and decide if our personalised English tutoring is the right fit for their learning needs.

You can contact us either through our email at tutor@goldstandardacademy.com or call us at 0481 336 988